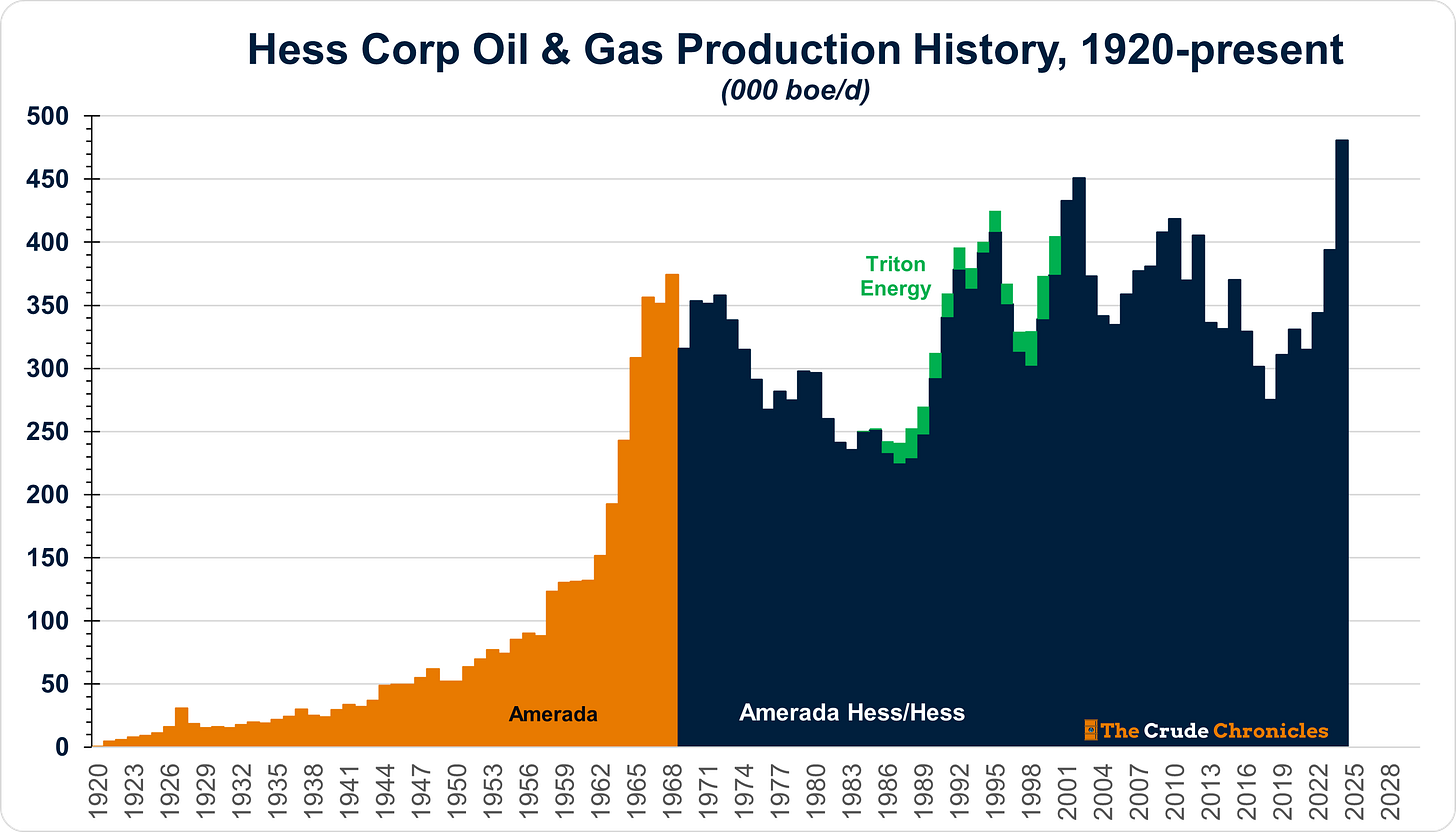

The Gist: This post is a financial (maybe farewell) history of Hess while we await arbitration decision in next month.

Part of me hates writing these historical farewell posts. These companies don’t just date back to the early days of the industry—they are the industry’s history. And with each one that disappears, there are fewer and fewer Crude oil companies left to Chronicle.

Hess wasn’t always the darling of E&P land.

In fact, Hess didn’t even start out as an exploration and production company.

The story begins with Leon Hess, the embodiment of the American Dream. A Lithuanian immigrant, he started by delivering fuel for his father’s business. After surviving the Great Depression, he founded Hess Oil & Chemical (Hess O&C)—a company rooted not in drilling, but in downstream operations: distribution, marketing, and refining.

And here’s a twist that would make a SPAC sponsor blush today:

Hess O&C became a publicly traded company not by IPO, but by acquiring a tractor company—Cletrac Corp.

The year before the deal, Cletrac had offloaded most of its tractor assets. But for Leon Hess, that wasn’t the point. The prize was Cletrac’s NYSE listing.

Hess’s entry into the world of E&P came through Amerada Petroleum, a company with roots in some of the most legendary names in early oil history.

The financial muscle behind Amerada was Weetman Pearson, later known as Lord Cowdray—a British industrialist who played a pivotal role in developing Mexico’s oil industry in the early 20th century.

The technical brain? None other than Everett DeGolyer—the geophysicist who brought seismic technology to the oil patch. His influence still echoes through the industry today via the globally respected consultancy DeGolyer & MacNaughton (HERE).

Amerada was essentially created to give DeGolyer a real-world laboratory—to test and prove his seismic theories across the resource-rich basins of the U.S. and Canada. The name “Amerada” itself nods to that ambition: America + Canada.

At its peak and before the days of Berkshire, Amerada was one of the highest-priced stocks on the NYSE.

By the early 1960s, Amerada was a company in decline—its reserves were dwindling, production was falling, and even Everett DeGolyer’s own firm, DeGolyer & MacNaughton, had revised its reserve estimates downward by a staggering 100 million barrels.

Attempts to sell the company to SOHIO (Standard Oil of Ohio) and Ashland Oil & Refining both fell apart.

Enter Leon Hess, who executed a play that would set off alarms in today’s corporate governance world. While sitting on Amerada’s board, Hess quietly acquired a 9.7% stake in the company—purchased from the Bank of England. He eventually made the winning bid, completing the acquisition and transforming Hess into a small, but integrated, oil and gas company.

At the time, growth in U.S. oil was stagnating. The real action was overseas—particularly the Middle East, dominated by the Seven Sisters. So when King Idris of Libya opened up bidding for oil concessions, Amerada didn’t hesitate. It joined the Oasis consortium, a partnership with Conoco, Marathon, and Shell.

At its peak, Oasis controlled acreage in Libya equivalent to twice the size of the state of New York.

And here’s a fun bit of vintage oil industry culture: back then, companies would boast about their undeveloped acreage like it was gold. Developed or producing acreage? Meh. What mattered was the potential. Reserve accounting rules hadn’t yet arrived, so Wall Street ran on dreams and land maps.

U.S. oil production peaked in the early 1970s, just as Libya—under Muammar Qaddafi—moved to nationalize his nations oil industry, forcing Western companies to pack up and look elsewhere. With OPEC tightening its grip and political risk rising, the next frontier for many was clear: non-OPEC basins.

For Hess, that meant shifting focus to the emerging opportunity in the North Sea—a harsh, capital-intensive environment, but one that offered geopolitical stability and massive untapped reserves.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Crude Chronicles to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.